1867 - Panorama du 4me district, Theodore Lilienthal

1865 - Steamboat Passing Faubourg Washington by Edward Everard Arnold

Faubourg Washington

The history of 906 Mazant Street began in earnest with the development of Faubourg Washington during the first half of the 19th century. As we learn from secondary sources, “David Olivier built a distillery in 1819. It was located on the levee between Mazant and Bartholomew, at the corner of Mazant. The distillers for these plants resided nearby. Olivier’s distiller, John Dougherty, lived on the levee near Independence and the Periet’s distillers, Benjamin and Prosper Gerardin, lived at 214 Levee, just above the Levee Cotton Press.”1 Olivier himself lived on the property, in a home at the corner of Chartres and Mazant Streets (4111 Chartres, demolished). On April 12, 1833, Olivier sold the distillery, his house, and two arpents of land facing the river to Etienne Carraby. These two arpents supplemented 1.5 arpents Carraby already owned to form the Faubourg Carraby, stretching from Alvar to Mazant. Even in these early days, Faubourg Carraby was administered along with Faubourgs Daunois, Montegut, De Clouet, Montreuil, and De Lesseps as part of a single administrative unit known as Faubourg Washington.

Faubourg Washington, like the plantations which formed its basis, extended back to about the location of the Florida Avenue Canal. These lands in the extreme rear of the faubourg were still thickly wooded, swampy, and inhospitable to most settlement. So thick was the forest at this point in the development of the city that residents did not refer to Lake Pontchartrain as the back of the city but instead to “the Woods” or “the swamp.” A Daily Picayune article dated October 30, 1846 describes the journey of several slave owners into “the swamp in the faubourg Washington,” where the men hoped to “[break up] a considerable gang of runaway negroes [who] had congregated” there [1846-10-30 Breaking Up a Gang - Maroonage in the Faubourg Washington].2 The members of the “gang” were, in actuality, men and women who had escaped slavery in New Orleans and sought refuge in the swamp. While the contemporary newspaper article reveals that the escaped slaves survived “by thieving and contributions upon their friends in the city,” a much more detailed picture of maroonage now exists in historical scholarship.

Faubourg Washington served as a place of inspiration for at least one artist. In 1865, Edward Everard Arnold painted a majestic craft slicing through the waters of the Mississippi River in front of Faubourg Washington. Analysis of Everard’s painting suggests that he may have painted from the vantage point of the West Bank. On the right side of the painting can be seen three Creole townhouses built of brick. These three homes resemble the two buildings still standing on Chartres Street, between Port and St. Ferdinand, backed by Architect’s Alley. Without examination of Everard’s diaries or other supporting evidence, we can’t say for sure exactly where Everard painted.

Mazant Street

The experience of Mazant Street during the 19th century included tales of robbery, murder, gambling, and a good deal of drinking. Small slices of life in the faubourg can be gleaned from various newspaper articles of the era. These articles trace part of the process of bringing Mazant Street up to prevailing civic standards. We learn that the City Council deliberately decided not to provide plank sidewalks for the residents of Mazant Street [1855-03-30 No Plank Sidewalks for Mazant Street]. Less than a decade later, the citizens were rewarded by the occupying Union military government with repairs to the unpaved street [1864-10-19 Repairs to Mazant Street].

“The experience of Mazant Street during the 19th century included tales of robbery, murder, gambling, and a good deal of drinking.”

Just after the Civil War, Mazant Street finally got a break, with the inclusion of a stretch of the street on the “down-town levee City Railroad” [1866-02-05 Mazant Street on Streetcar Route]. In fact, the streetcar ran right past 906 Mazant at one time, on its way from N. Rampart Street to the Levee. The New Orleans Crescent newspaper reported upon the City Railroad as “one of the most important and useful...internal improvements of New Orleans” in the months just after the close of the war. The Crescent praised “the old and staunch City Railroad Company, who invested their capital and energy in the then new and financially hazard enterprise [i.e., railroads]” and claimed that the downriver communities were “one of the most important sections of the city.” In truth, the downriver communities were looked upon by the rest of the city as inefficient, corrupt, and foreign. A legacy of the era of New Orleans politics when the city was divided into three separate municipalities, each with its own Municipality Council but a single, common Mayor, the view of the Third Municipality (from Esplanade Avenue to the St. Bernard Parish line) ensured that the downriver communities remained rural, residential, and isolated.

That the City of New Orleans chose to connect the Third Municipality to the old city center via a streetcar system as one of its immediate goals after the Civil War suggests a concerted attempt to unify the city by lessening the isolation of its most distant reaches. Consider, as well, that the City Council did not even consider a proposal to open Burgundy Street (then called “Craps Street”) between Mazant and France streets until 1868. Burgundy Street simply stopped into a dead end at Mazant Street. Even though the street had appeared on maps since at least the 1820s, neither the City of New Orleans nor the Third Municipality government ever cut a street through to France Street.

July 12, 1918. Obituary for Angel Liere, 906 Mazant.

1896 D. A. Sanborn, the Sanborn Map Company (page 351). Used as the primary fire insurance map company for over 100 years.

Construction History

In the chain-of-title, we find evidence of houses and other structures on the property which predate the present house. Giovani Fassio purchased six lots from Ernest B. Fassio [relation?] on January 31st, 1857 [Octave de Armas, NP]. The 1857 purchase included “a house with four rooms, two cabinets, galleries, kitchen [with] two rooms, stable and a fine garden and fine fruit trees.”3 These lots stretched half the frontage on Mazant Street, just slightly wider than the lot in its present form down to about present day 918 Mazant Street. We can see the extent of Fassio’s property on a map drawn by Horatio L. Gilbert on April 30, 1943 [Marion G. Seeber_ 28May1943 (5)]. On Gilbert’s plan, we also see the rear of 906 Mazant, which straddles lots 18 and 19, connecting to a shed on Lot 17. Another shed abuts the rear of the property, while 4023 Burgundy Street is nestled in the same corner it has occupied for decades. Two other items in the Marion G. Seeber act of sale describe all of the contents of 906 Mazant Street at the time of the death of Anna Catherine Liere [see Marion G. Seeber_ 28May1943 (6) and Marion G. Seeber_ 28May1943 (7)].

Henry Liere gradually accumulated property in the area before building 906 Mazant, in 1884-85. His name appears on the tax assessment rolls as the owner of multiple properties in present-day Bywater as early as the beginning of the 1870s. His business interests included ownership in insurance company stock, as well, as evidenced by a classified ad placed by Liere in the October 25, 1879 edition of The New Orleans Democrat newspaper. The ad read, “Lost of Mislaid – Fractional certificate of stock of the Merchant’s Mutual Insurance Company, of New Orleans, for $56.40, issued July 16, 1872, in the name of Henry Liere, No. 167. Application made for a duplicate thereof. – HENRY LIERE”4 [1879-10-25 Lost or Mislaid - Henry Liere].

We used the Tax Assessment records of the City of New Orleans to fix the date of construction of 906 Mazant in 1884-1885. The assessment marked “1883-1884 Tax Assessment – New Buildings” indicates both an increase in the assessed value of the property from $850 to $2,750 and a notation by the tax assessor reading “New Buildings” in the “Remarks” column [1883-1884 Tax Assessment - New Buildings]. These two pieces of information offer indisputable proof that the house at 906 Mazant Street was there in 1884. The next year’s assessment [1884-1885 Tax Assessment - R by BA] shows an even greater increase, from $2,750 to $4,000 (approximately $95,000 in 2017). The assessor noted that Liere also owned some sort of vehicle or carriage for which he was assessed.

The notation in the “Remarks” column of the 1884-1885 assessment is cryptic. It reads “R by BA.” It could refer to the vehicle or to the real estate property. Whatever it means, it justified an increase in the value of the property of $1,250, only part of which could be attributable to a vehicle, even an automobile. Indeed, although various versions of motor vehicles existed in 1885 and electric automobiles were first raced in New Orleans in 1901, it is not clear that anyone in New Orleans owned one in 1885. 5 Another possibility for the meaning of “R by BA” comes to light when we examine the 1885-1886 Tax Assessment. This later assessment says “R 3000” under the column 5, labeled “Money loaned on interest or in possession, all credits and all Bills Receivable for Money loaned or advanced.” Does the “R 3000” note indicate that Liere was being taxes for $3000 worth of Receivable money in 1886? Under column 8, the heading reads”Number of shares of each stock holder in all banks or Banking Associations in this State.” Does “BA” indicated a Banking Association? Does “R by BA,” therefore, mean that Liere was due to receive money from a Banking Association? Without a complete review of the entirety of the tax assessment records for the period, we’ll likely never know.

1883 Robinson Map, plate 20

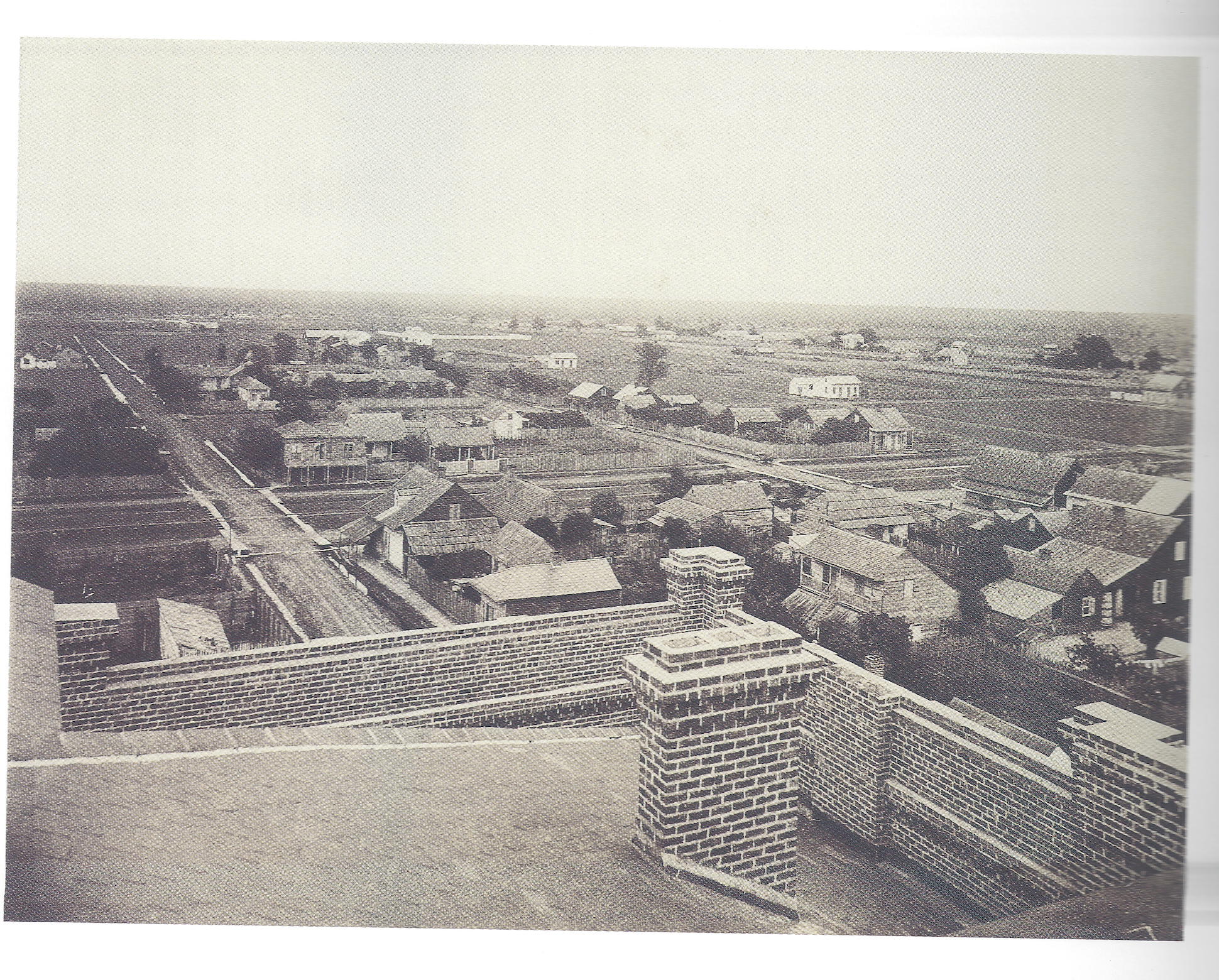

The 900 block of Mazant does not appear on the earliest Sanborn Maps of the city, owing most likely to the sparsity of development in that section. Even though Theodore Lilienthal’s 1867 photograph of the Third District [“1867 - Panorama du Troisieme district, Theodore Lilienthal”] shows an appreciable level of development facing out toward Gallier Street, we may presume that Mazant Street appeared more like the view “1867 - Panorama du 4me district, Theodore Lilienthal.” Indeed, the picture claiming to depict the Fourth District actually shows the area above St. Claude, in the Third District, according to Gary Van Zante’s book on Lilienthal, New Orleans in 1867. The two Lilienthal photographs were both taken from the roof of the Academy of the Marianite Sisters of the Holy Cross, which takes up the square bounded by St. Claude Avenue, Congress Street, Gallier Street, and N. Rampart Street. The “Troiseime District” photo faces the upriver, toward the river. The photo claiming to be the “4me District” actually faces downriver, toward Lake Pontchartrain.

The style of houses making up the built environment in the old Faubourg Washington reflected the predominant economic status of the residents of the neighborhood at that time. Lilienthal’s photographs, in company with the Robinson and various Sanborn maps, show small cottages, workshops, and corner groceries speckling the man-made cityscape. In this respect, Henry Liere’s construction of 906 Mazant in the 1880s must have been a momentous occasion in the neighborhood. Even then, it would have been the grandest home for blocks. In point of fact, 906 Mazant was the only two-story house within the nine blocks depicted on this page of the 1896 Sanborn Map [after 1896, the Sanborn maps typically attributed attic space as a half-story, thereby changing its description of 906 Mazant and similar building types from 2 to 2.5 stories]. Perhaps one reason for this is the fact that the streets in the neighborhood were not yet paved! Though 906 Mazant Street is no longer the largest structure on the 1908 Sanborn Map, the streets had still not been paved nearly a decade into the 20th century.

“In this respect, Henry Liere’s construction of 906 Mazant in the 1880s must have been a momentous occasion in the neighborhood.”

By the time the Sanborn Company published its map in 1937, New Orleans had experienced some of the progressive spirit which swept the nation in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Even though the Great Depression took hold of many in New Orleans, the Liere-Messina family maintained its preeminence in the built environment of the neighborhood until the death, in 1943, of Anna Catherine Liere, widow of Victor J. Messina, grand-daughter of Henry Liere.

According to the 1883 Robinson Map [1883 Robinson Map, plate 20], barely two dozen houses fronted Mazant Street between the river and St. Claude Avenue. The scene must have looked very much like that in Lilienthal’s image of the lake-side of St. Claude.

By 1896, however, Mazant Street had grown. Henry Liere’s great mansion at 906 Mazant Street certainly demonstrated strong confidence in the development of the neighborhood. Even in the 1880s, such houses seemed more at home in the Fourth District (today’s Garden District) than in the less affluent Third District. We see on the 1896 Sanborn, as well, the small cottage that still stands in the side yard of 906 Mazant. The cottage is labeled as 4023 Burgundy Street in this map, laying in the rear of a double- shotgun house at 900-902 Mazant.

The Liere-Messina Family

Anna Catherine Liere married Victor J. Messina. Messina was a noted businessman in the city. During the second quarter of the 20th century, the Messina’s lived at 906 Mazant Street. In 1931, Messina sued the New Orleans Public Service, Inc. (NOPSI) after two of its employees removed his electric meter without permission. The Times-Picayune reported that “the employees...called at the house Monday afternoon and without legal or just cause removed the meter from the premises and deprived him of the further use of electric current” [1931-05-14 Removal of Light Meter Brings Suit - Victor Messina].

Messina was among a gaggle of national politicians and businesspeople who were treated by a company trying to sell paved roads [1912-10-20 Good Road Plan, Victor Messina on Trip 2pp]. In a way, Messina’s involvement in state infrastructure projects harkens back to the days of Mazant Street residents petitioning the city government from better road conditions. The 1912 “Good Roads” sojourn shows clearly, as well, how quickly Messina rose to prominence in the business community. Only in 1898, Messina had been arrested for illegally selling liquor on a Sunday [1898-11-12 Victor Messina Admits Selling Liquor on Sunday, convicted]. In New Orleans in those days, the city enforced a “Sunday Closing Law” whereby no establishment in the city was permitted to open between 12:01 am and 11:59pm on Sunday. Many establishments simply reverted to “members-only” rules on Sunday so business never really stopped. With widespread flouting of the law, many dispensed with such formalities, a protest that nevertheless opened them up to arrest. Messina, it seems, fell victim to just such a circumstance.

Compiled by Greg A. Beaman, "906 Mazant – a brief history," gregabeaman.com